Since the advent of internet accessible Artificial Inteligence, AI, there has been a good deal of angst and breast beating about the future roll of human beings in the scheme of things. An example is a recent TEDx talk by Scott Aaronson: The Problem with Human Specialness in the Age of AI .

48,699 views Mar 9, 2024

In his compelling TEDx talk, Scott Aaronson confronts the prevalent notion of human exceptionalism in the era of artificial intelligence. As a distinguished figure in quantum computing and computer science, Aaronson examines the challenges and implications of clinging to the belief in human specialness amidst rapid AI advancements. With sharp wit and intellectual depth, he navigates the audience through the evolving landscape where machines rival and sometimes surpass human capabilities. Aaronson questions the assumptions that underpin our understanding of intelligence and explores the psychological barriers hindering our acceptance of AI as a formidable creative force. Scott Aaronson’s exploration of The Problem with Human Specialness in the Age of AI invites us to reconsider our relationship with technology and reevaluate the narratives shaping our collective future.

Much of Aaronson’s talk is concerned with projections and possibilities and I was left wondering whether AI is really quite the threat that he suggests and whether it really is “intelligent” in the way in which ordinary people use that word. It is certainly brilliantly fast and effective at tasks which it has “experienced” in its “training set” and it has experienced a very large training set.

My interaction with AI has been with ChatGPT 3.5 which is readily acessible. It has certainly provided me with clever and useful answers to questions I have asked it in my own field of physics, although its answers tended to be “conventional wisdom” in tone, as if it had read all the best text books and memorized them (which it has). If you ask it a question, expect a textbook answer – it is a user-friendly front end to Wikipedia.

Hence I thought it might be interesting to ask a well known problem in a form which does NOT appear in any text-book. I chose Euclid’s proof that the square root of 2 is not a rational number, that it cannot be written as a fraction as the ratio of two integers with no mention of Euclid or rational numbers. Can it do as well as Euclid by reason alone without any help from text books and conventional wisdom?

So I asked it to do the following:

Find the smallest pair of positive integers (a,b) such that (a/b)^2 = 2

To my astonishment ChatGPT came back with utter garbage, viz.:

One obvious solution is when a = b = 1, but it doesn’t satisfy the condition that a and b are positive integers.

Another solution is a = 2 and b = 1. Let’s check if it satisfies the equation:

a^2 = 2 * b^2

2^2 = 2 * 1^2

4 = 2

The equation holds true. So, (a, b) = (2, 1) is a solution.

In other words, ChatGPT told me that (2/1)^2 = 2 because 4=2 which is true!

When I pointed out that 4 = 2 is not true, ChatGPT aopologised and told me that it was due to “human error”. I challenged this statement as well. Further apologies ensued and ChatGPT finally started talking about irrational numbers and Euclid’s proof.

The complete conversation is reproduced here: Root2.pdf

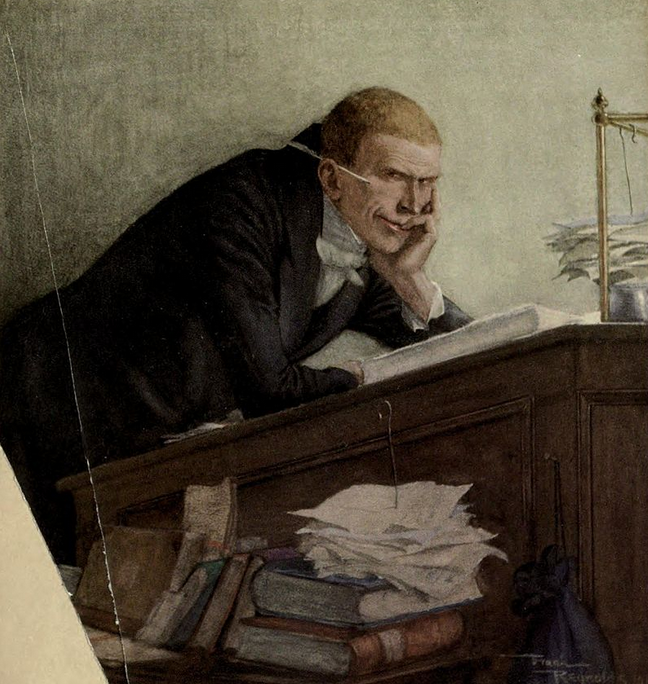

I find it impossible not to anthropomorphise ChateGPT and in doing so I am left with the impression of a thoroughly dishonest and excessively obsequious human being who resembles Dickens’ Uriah Heep. Hence the image at the top of this post.

Our final exchange was this.

You would agree then, that your output should always be checked by a human in case such mistakes are made.

Absolutely, it’s always a good practice to verify the output of any system, including AI-generated responses, especially when the information is critical or when there’s uncertainty. While AI systems strive for accuracy, they can still make mistakes, as demonstrated earlier. Human oversight is valuable for catching and correcting errors, ensuring that the information provided is reliable and trustworthy. Thank you for highlighting the importance of human involvement in the verification process.

So the answer is this. We humans are not irrelevant; our function is to keep AI honest.

Editor’s Note: There has been an interesting discussion on Facebook in addition to the comments below. I have transcribed the Facebook comments into the next post.

My recent interaction with AI mirrored your experience- I too had a role in the “verification process”.

Have you used a different IP address to see if the program actually learned from your interaction with it.

Thanks for highlighting your experience!

Mark Miller

Thanks for the suggestion Mark. An excellent idea. I only have one IP address available. Could someone else do that experiment please and let me know the result?

Thanks John,

Regarding AI, I wonder if there’s an equal advantage to those with criminal intent to get an enhanced freedom in the cyber realm to pursue their wicked ways.

And what of the capital and energy costs of handling so much of what is often trivial data..

Perhaps distributed ledgers will also lead to their own constraints at some point. How much resources are consumed in a country like say China with widespread facial recognition and social credits. The brave new world is fast upon us.

Cheers

Rob K

I am not a fan of Chomsky, but he is dead right on this one. Thanks Trevor.

One of the cleverest tricks played on an AI chatbot I have ever seen. Well done John.